Art and pain: Inherently inseparable or artificially linked?

With great art often comes equally great pain— take a look into any creative art form and ample evidence abounds.

Consider Van Gogh, for example, a man responsible for some of the most well-known and well-respected pieces of art. With his artistic ability, unfortunately, came horrible mental illness, so severe, in fact, that he cut off his ear during one particularly intense episode and eventually killed himself shortly after his 37th birthday.

Or, Virginia Woolf, who penned A Room of One’s Own, which is acknowledged as one of the most integral pieces of feminist literature, and The Death of the Moth, an insightful essay still applauded for its metaphors and hauntingly beautiful prose. Woolf, like Van Gogh, faced immense psycho-emotional turmoil, plagued so much so that she walked into a river at the age of 59 and did not walk out.

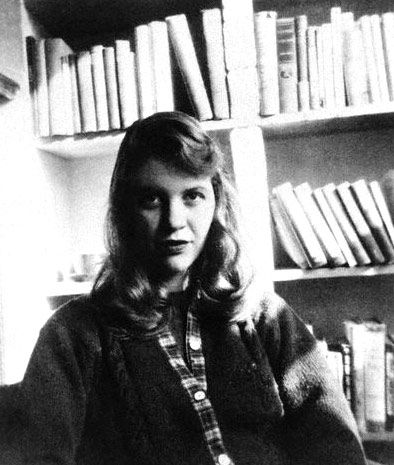

The tragic trend continues with Sylvia Plath, the woman to whom we accredit The Bell Jar, the genre of confessional poetry, which includes classics such as “Mirror,” “Lady Lazarus” and “The Hanging Man,” the stream-of-consciousness narrative, and, quite frankly, most all things even vaguely melancholic. Plath, again immensely emotionally plagued, met her demise by sticking her head in the oven at 30.

Finally, for those who prefer a more modern example, consider Kurt Cobain. He, along with the help of his Nirvana bandmates, flipped the entire music industry on its head in the early 90s, forever transforming the grunge-rock scene. But, somehow, he too fell prey to the supposed interconnectivity of art and pain, shooting himself in 1994 at just 27-years-old.

Are these instances— which constitute only a fraction of suffering-induced art— mere coincidences, just uncorrelated flukes confirming nothing further than the often fatalistic effects of mental illness? Or are they proof of the apparent— though not necessarily inherent — interconnectivity of great art and great pain? For two reasons, the latter is exponentially more plausible than the former:

First, in order to be considered somewhat “universally great,” art must relate to the masses, and nowhere is a more relatable topic found than in the inevitable human phenomenon of pain.

The primary reason that Woolf’s The Death of the Moth strikes such a chord with readers, or Cobain’s “Heart-Shaped Box” elicits such an emotional response from listeners is because both Woolf and Cobain tap into their own pain, effectively channeling the pain of their audience. It’s relatively implausible to assume that Cobain would have reached the same level of success if he sang about love and happiness rather than heartache and angst. It is relatively plausible, however, that he would still be alive if his life— and, in turn, his art— would have been centered around the more joyful of those two options rather than the more dreadful.

The second, but no less valid reason lies in the all too frequent romanticization of the “tortured artist” stereotype, along with its accompanying mental illnesses.

Unfortunately, because such phenomenal and groundbreaking art is— and, arguably, always has been— created by the most tortured individuals, artists (along with the majority of society) have conflated the idea of art and pain so much so that the two have become one entity. That conflation is not inherently a bad thing— because of it, art becomes an escape from pain, a coping mechanism.

Recently, however, one more aspect has been added to that conflation that transforms the mindset into a harmful narrative: mental illness— more specifically, the romanticization of mental illness. This romanticization most simply means that, for those creative individuals not naturally affected, mental illness has become something to covet, something to obtain.

This mindset not only harms these envious individuals, but, more importantly, it harms those who actually are affected by mental illness. If those affected see that what they’re struggling with increases their chance of fame and praise, their incentive to get better decreases exponentially. After all, why would they voluntarily give up a mindscript similar to that of Plath? Why would they try to alleviate their pain? It worked for Van Gogh, right?

Essentially, with great art does come equally great pain. The most tortured individuals do create the most praiseworthy art. Pain and art are interconnected. However, that doesn’t signify that the two are inherently inseparable. Rather, it reveals that society believes them to be inherently inseparable.

If we, as a society, stop trying so hard to find art that relates to our pain and, instead, start taking steps to alleviate it, we can begin to end the “tortured artist” stereotype we unwittingly perpetuate daily and, in turn, separate the seemingly inseparable human phenomenons of art and pain.