How confirmation bias is ruining debate

Gun control. Immigration. “The Office” vs. “Parks and Recreation.” Many of the world’s most pressing disputes have been labeled eternally enigmatic, as if we’re meant to just surrender, allowing problems to exponentially worsen because society’s brilliant minds can’t reach consensus. Too many factors, too many viewpoints, too many arguments.

But what if there are right answers? What if they’ve been right here, under our noses all this time, and we’ve been too busy trying to prove ourselves right to notice?

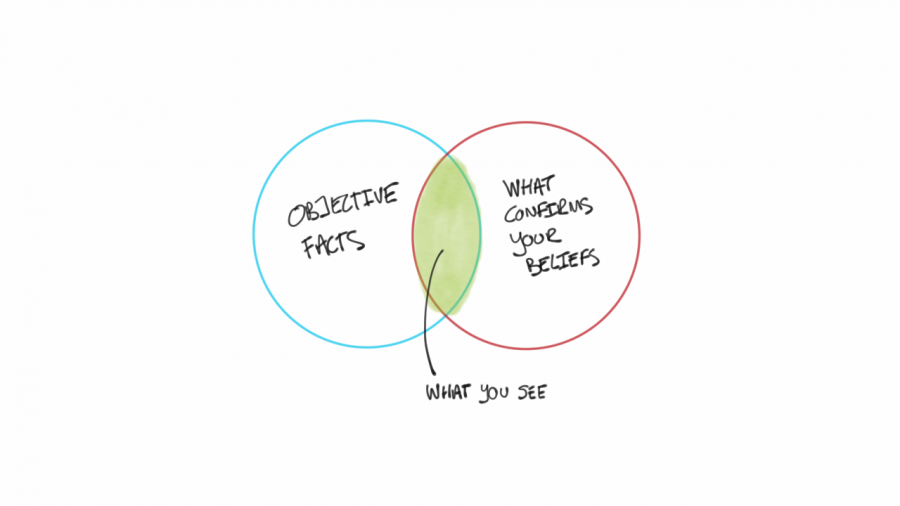

Confirmation bias is an isolated focus on evidence that confirms our existing personal beliefs, while failing to acknowledge any proof to the contrary. It’s the reason we can’t make important decisions.

“The desire to be right and the desire to have been right are two desires,” said philosophers Willard V. Quine and J.S. Ullian in “The Web of Belief,” their treatise on rational judgment. “The desire to be right is the thirst for truth, [and] there is nothing but good to be said for it. The desire to have been right, on the other hand, is the pride that goeth before a fall. It stands in the way of our seeing we were wrong, and thus blocks the progress of our knowledge.”

Any self-proclaimed champion of debate will tell you that argument is healthy, that it’s necessary for a progressive society and helps us better understand one another. This might be true in a perfect world, but not in today’s society, where omnipresent confirmation bias causes every well-meaning discussion to devolve into bickering and up-turned noses. We can’t expect debate to change the world if it can’t change one person’s opinion.

If Mr. Yanko has taught us anything, it’s that everyone is biased (some more than others, surely). Everyone has preconceived notions and personal beliefs that, consciously or unconsciously, influence their decisions. Even trying not to be biased can, in some ways, make us less objective.

So… can anything be done? Is argumentation completely pointless? Will we really never decide between Michael Scott and Leslie Knope?

I can honestly say I don’t know. But I definitely don’t want to stop trying.

Imagine: You’re sitting in the passenger’s seat of your best friend’s car, coasting at five miles over on the highway. Music hums incoherently at low volume as you make small talk, telling him all about what Susan from Pre-Calc said about your hair. The longer you rant, the angrier you become. Your friend tries to defend stupid Susan and, before you know it, you’re in the heat of a spirited debate on the nature of humans.

Yelling drowns out the music; not necessarily screams of anger, but certainly of passion. At one point, you yell for three minutes straight, name-dropping Thomas Hobbes and citing personal experiences so emotional your voice begins to quiver. You shout your closing statement, tears in your eyes, and the car goes silent. At some point in your tirade, he turned the music off; you never noticed.

You look at him. He looks straight ahead.

You get off at the next exit and arrive at a red light, still in silence. Your hands fidget in your lap and your entire body feels downright uncomfortable, as if saying so much made you a different person, one who doesn’t fit into this skin. You steal glances at him, praying to God he’ll say something, anything, so you don’t feel like such a freak.

Silence. More silence. And then, barely above a whisper, you hear it.

“You’re right.”

Exhilarating, isn’t it? Imagine the euphoria, the pure joy one might feel if the goal of pure argumentation was actually met: someone actually changing their perspective. It’s hard to picture in a society so set in its ways, but I’d like to think it’s at least possible.

If we aren’t mindful of confirmation bias–of our predisposition to do anything but change our minds–then all argument is really just an exercise in futility. But, if we constantly remind ourselves to honestly consider the opposition (and then actually do so), someone might actually feel that euphoria, that pure joy, that comes with finding an understanding.

This will be a difficult road. Oftentimes, you’ll have to be the one to bend. Concession and displays of understanding aren’t mere rhetorical tactics to build your credibility; you actually have to step outside your bias bubble, swallow your pride and yield. It won’t feel good in the moment, and probably won’t for a while, but it’s one step closer to a world of positive change.

Mr. Yanko • Dec 4, 2018 at 9:54 AM

Thanks for using my name in the same essay with Thomas Hobbes.