The evolution of the classroom

Ahh, the classroom. Whether a comfortable, air-conditioned heaven or a stale, muggy prison, it has always been the core of educational growth for adolescents and young adults.

Despite the ubiquitous purpose of the thought cubicle, its appearance has varied throughout history. The question is: How different was school in the past compared to today? For a crash course in the history of classroom characteristics, look no further.

Ancient Greece

Education in Ancient Greece varied throughout each city-state. In Sparta, for instance, boys were taught to fight rather than to read and write. In Athens, the focus was on athletics and fitness. However, the material included courses which prepared young citizens to become future voters. In other city-states, from the age of seven to 14 students were taught to read, write and complete simple math. They read poetry aloud and memorized every word by heart. After the age of 14, lower-class children were trained in a specific trade, while the wealthy children of Athens went to the Assembly, market place and gymnasium to learn from older citizens.

Schools were quite small. There was one teacher and around ten to twenty boys. Everything was memorized and when needed, wooden boards covered with wax served as their slates. They used wooden pens with a sharp end to write and a flat end to rub out any errors. Other than these materials and stools or benches, the classrooms were much more bare compared to those today.

Due to cost, only the rich could afford to have their children trained and educated by an instructor. While the young men adapted to physical classrooms, young women were taught at home, learning about housekeeping and taking care of the family. For Greek girls, school was a forbidden frontier and education its forbidden fruit.

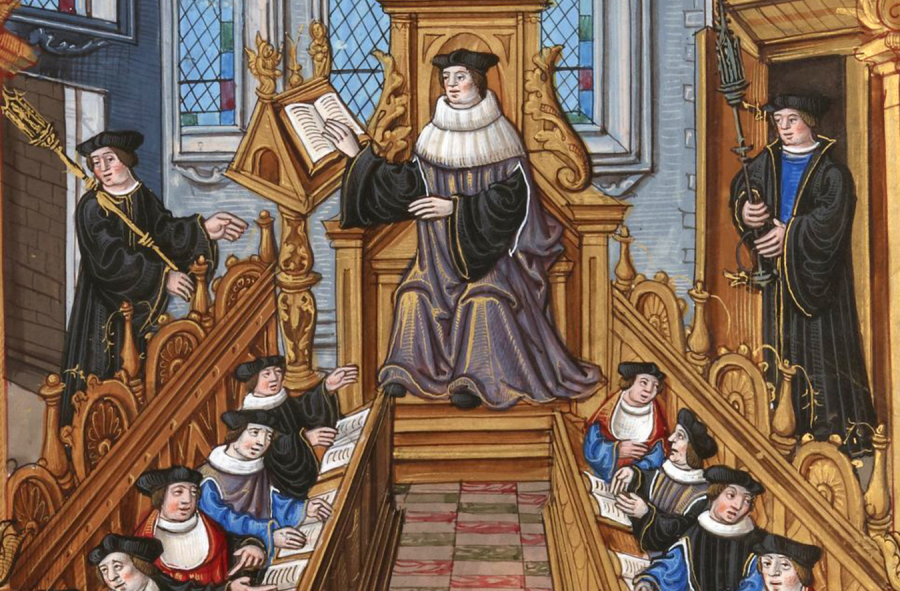

Middle Ages

In the 1300s, only 5% of the population in England was literate. Only wealthy young men were permitted to attend schools. Wealthy young women were barely literate and the only women who received any proper education were those who chose to become nuns. Education was a luxury for the noble sons of the age and there were even laws set in place to ban serfs from any sort of institution. However, kind, wealthy people who disagreed with the blatant biases of the day gave money to fund the education of those with promising talents.

There were three main schools which wealthy young men could attend. Elementary song-schools were headed by priests. Here, boys learned to sing Latin hymns and songs, and those fortunate enough to have educated priests learned to read and write. Monastic schools were centered around religious education. These schools were slightly more accepting towards those from lower-class families and allowed these children to work as servants in the monastery. Lastly, grammar schools were heavily focused upon Latin grammar, with lessons about rhetoric and public address. Mathematics and science were often neglected and barely any time was spent on these subjects.

Renaissance

In the beginning years of their education in Italy, students studied at home. The wealthy hired tutors within their household. Women were also taught certain subjects, but this education was accessible only to the affluent or members of the nobility. While arithmetic was limited to those from wealthy households, subjects like latin, geometry, science and astrology were taught to a wide range of students. Also, poetry, philosophy and grammar were heavily prioritized for all educated young adults.

Latin was an essential language during this time period, and children were introduced to its grammar at the age of five. The wealthy were expected to incorporate Latin into their daily conversations in order to mark their class and rank. The usefulness of geometry was limited to those seeking to become military commanders. On the battlefield, geometry could be used to trace the trajectory of a cannonball or measure the distance from one point to another. Astronomy, on the other hand, was seen as practical for any profession, as it was believed that the stars could tell people about themselves and the future. Furthermore, it was useful for understanding classical poetry of the day, which detailed allusions based upon astrological images.

Educational Reform in the 1800s

During the 1800s in the United States, public schools were established for people of all social classes and religions. Created by Horace Mann, an education reformer, this system encouraged what were referred to as “common schools”. These schools were funded by local taxes and headed by a school board. Because of local funding, education was no longer a luxury of the wealthy but open to poor, middle-class and wealthy students. Children of all ages and grades (including young girls) were taught by one teacher in a single classroom. They studied reading, writing, arithmetic, history, geometry and math, much like we do today. Soon, these schools began to outnumber private schools.

Unfortunately, while these schools did accept students from multiple social classes, they excluded people of color. However, during the late 1860s and 1870s, the Freedmen’s Bureau was established. Acting to serve newly-freed African Americans, the Bureau spent $5 million to open 1,000 schools in the South for Black students. The enrollment number grew to over 90,000 by the end of 1865. The curriculum and education throughout those schools resembled those found in public schools in the North.

Any visions of schools as they are today were not possible until 1954, through the Supreme Court ruling of Brown v. Board of Education which ruled segregation in schools to be a violation of the 14th Amendment. Through the bravery of the Little Rock Nine, schools slowly blossomed into more diverse institutions.

As educational discoveries have been made throughout history and as schools have opened their doors to those of all races, genders and social classes, the educational experience – whether air conditioned or not – has advanced to what it is today.